The questions every corporate innovation leader asks about culture, answered

Thomas Brown & Herminia Ibarra

30 November 2021

Creating an innovation culture is a complex task of orchestrating people, teams and mindsets, and no matter how many management books you read it is always unpredictable. There are certain aspects that seem to trip organisations up time and time again — get these right and you have a fighting chance of success. Sifted put the most common questions they hear from corporate innovation leaders to Herminia Ibarra.

Why is culture change so often an afterthought when it comes to innovation?

“It’s certainly not ignorance — I often ask the executives I teach at London Business School about their role in leading change, and the majority will cite culture and mindset as their primary focus or challenge. So they know it’s a factor, and they know it’s important.

Unfortunately, too many executives don’t see culture change as central to their role. It’s amorphous, it’s not always tangible, and it’s too often seen as a ‘programme’, with slogans and statements of intent.

Microsoft changed how people were appraised, how they were rewarded, and who was promoted. People throughout the organisation got the signal.

In fact, it’s got everything to do with who leaders value, what they reward, who’s in the inner circle, who gets promoted, what behaviours they model and what behaviours are reinforced by the systems, processes and ceremonies of the organisation. That’s why it’s so important for leadership teams collectively to own the cultural agenda in their organisation, rather than relegating it to a department such as HR.”

There’s an old adage, ‘What gets measured, gets done’. How important is it to link culture and compensation?

“If I were advising a newly-anointed chief innovation officer, I’d suggest that one of the first questions of their organisation should be around how people are measured and compensated. We talk a lot about alignment when in fact one of the most straightforward and effective ways of achieving it is to align rewards with what you want people to do.”

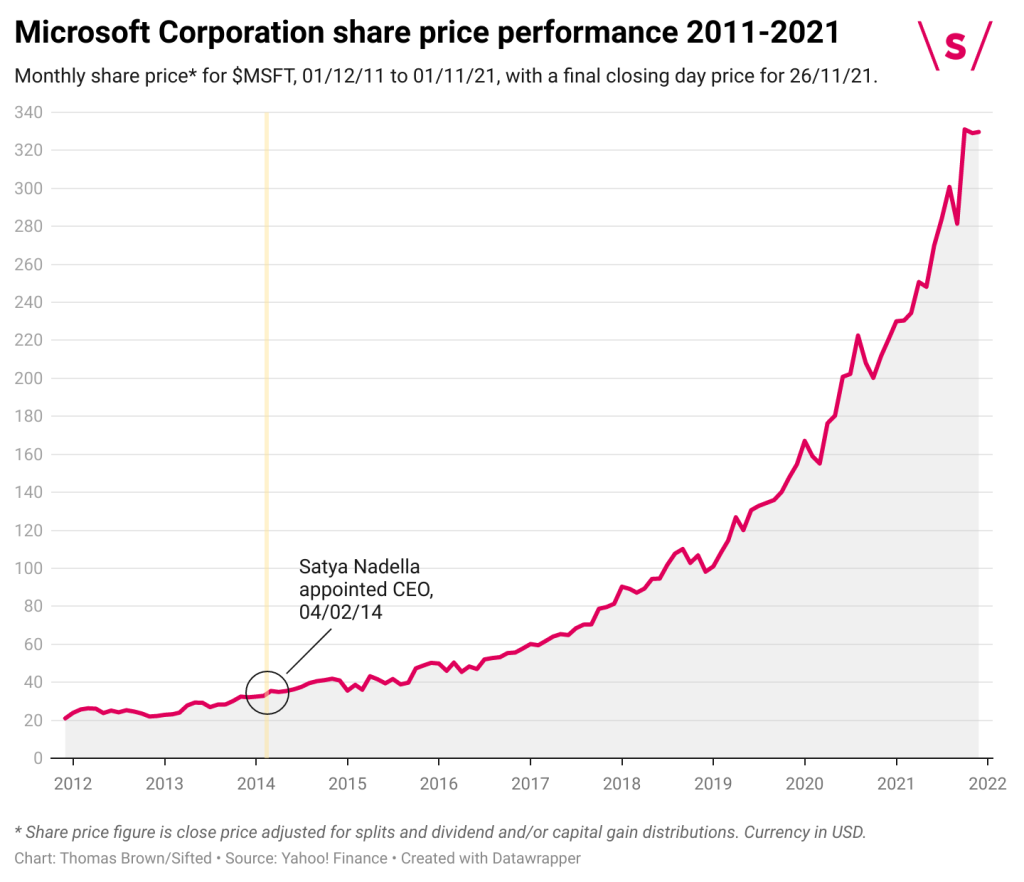

Ibarra points to the cultural transformation at Microsoft since Satya Nadella took over as CEO almost a decade ago, citing it as one of the few examples of an organisation that has invested intentionally in building an innovation culture — and that has the financial results to evidence its success.

Two changes stand out as having had a significant impact on culture change.

“They changed their performance review process right from the start. They recognised that innovation was more of a team sport than one which required individual stars, so they refocused performance evaluation more on how an individual contributed to a team’s business impact. As the transformation unfolded, Microsoft got to a point where revenue was split approximately 50:50 between its ‘legacy’ business, based around software licensing, and the new business model centred on cloud-based products and services, and innovating in the latter. The leadership then decided to set their compensation weighted 90:10 in favour of products, services and innovation based in the cloud, rather than their legacy business.”

“Combined, these two moves changed how people were appraised, how they were compensated, how they were rewarded, and who was promoted. Eventually, people throughout the organisation got the signal.”

How can leaders avoid the culture clash between the ‘new’ and the legacy organisation?

“This is potentially really difficult, and few organisations get it right. Managing an established cash-cow business alongside a new one which may well cannibalise it is a tricky balancing act, and the creation of separate units to manage these was an idea widely propagated by Clayton Christensen’s book The Innovator’s Dilemma.

While this approach has its merits, a common downside is a ‘not invented here’ mentality, and finding that the benefits of the new culture you form never really contaminates the established business. But what can help to make the difference is to ensure that people are able to float between the two — the established business and the new innovation unit.

Managing an established cash-cow business alongside a new one which may well cannibalise it is a tricky balancing act. At some point, you’re going to want the culture of experimentation to permeate the established business. You’re going to want the characteristics that you’re nurturing in the innovation unit, those which are having a positive impact, to catch on elsewhere in the business, so the benefit is more widely realised. And at some point, you’re going to want to automate aspects of the established business, to bring it into the age of artificial intelligence, to modernise it and to future-proof it as well. It may not be the ‘new thing’, but it still services customers and still creates value, and therefore still requires attention.

If you put in place that flow of people between the two worlds you’ve created, you’ll have a cadre of people who understand both, who understand what’s important about both and understand the constraints of both. That will go some way to helping avoid culture clash or rejection.”

Can innovation succeed without the CEO?

“No. Building an innovation culture will not succeed without the leadership of the CEO. Period. We recognise and celebrate that in start-ups, culture comes from the founder. When the company is young, it’s very palpable…it’s intrinsic in what’s rewarded, what’s punished, what gets attention, what the founder is maniacal about. For some reason, though, we see a diminished role for the CEO in a large, established enterprise, when in fact culture is still a manifestation of what the most senior person values and pays attention to, and what she or he spends most of their time on. So the CEO is more than just a figurehead when it comes to innovation — a mandate for someone else to run with it won’t be enough.”

So how can the CEO best support innovation, and the evolution of company culture to support it?

“The CEO needs to give people businesses to run that align with the strategic imperative for the organisation — in this case, reflecting the importance of innovation. They need to create and defend resources for ‘the new’, and they need to provide cover for when things go wrong — and if you’re innovating, not everything is going to go right, or right first time. They also need to provide signals for what the organisation values.”

Ibarra points to a further example from Microsoft, in a change to its quarterly business review process. Like most organisations, Microsoft ran on a cycle where four times a year there would be a big review meeting, one of which would usually be particularly important. They realised that they were pouring vast amounts of manpower, attention and money into preparing for what had become, in essence, corporate theatre. Everybody knew the figures anyhow, because they had smart dashboards and real-time numbers. But they kept on putting on these big shows.

“They’d start preparing months in advance, the one in February would ruin everyone’s Christmas, there’d be meetings to prepare meetings, huge decks of PowerPoints just in case. It becomes an opportunity for people to look good, to show how on top of their business they are. It becomes a show. Learning and vulnerability — these are things you need if you want to build a culture of experimentation. But there’s never a conversation about what went wrong, what’s been learned, what could have been done differently. It doesn’t become a learning moment, it’s not a place where you can show any vulnerability — and these are all things you need if you want to build a culture of experimentation.

After a while, they realised they were sending a mixed message, so they changed their entire approach to quarterly reviews — and people were immediately relieved! You basically end up in the production of PowerPoint slides and the production of justifications, rather than engaging in learning conversations — which is what you need to do when you’re innovating.”

How do you know if an organisation is really ready to change?

“If you’re charged with leading innovation, whether it’s a fresh assignment or a fresh employer, I’d start by asking the CEO and the board these five questions. Their answers, or lack thereof, will be telling.”

- Have you tried this before?

- What worked, and why?

- What didn’t, and why?

- What’s going to be different this time around?

- What are you prepared to do personally to support it?

Ibarra says if your CEO can’t give you a frank reflection on past efforts, mis-steps, and lessons learnt, then you’d be wise to question whether the organisation’s leaders are committed to changing the status quo. If they can’t give positive assurances of how and why their innovation agenda will stand a better chance of success today, versus the past, it may foretell a difficult path ahead. And if the CEO hasn’t already contemplated their personal contribution to making innovation a success, extracting commitments may prove a challenge down the line. Equally, a complete and considered set of answers may be just the building blocks you need.

Either way, they’re five sensible questions to pose to each member of the executive committee. Any differences in response will give you great fodder for an early discussion about the innovation path ahead.

Read the original article on Sifted.