Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader

Herminia Ibarra

22 May 2015

In this excerpt from her book, Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader Herminia discusses what she describes as the ‘outsight’ principle: the cycle of acting like a leader and then thinking like a leader; change from the outside in. She argues that people become leaders by acting their way into a leadership position.

The ‘outsight’ principle: how to act and think like a leader

“I’m like the fire patrol,” says Jacob, a 35-year-old production manager for a mid-sized European food manufacturer. “I run from one corner to the other to fix things, just to keep producing.” To step up to a bigger leadership role in his organisation, Jacob knows he needs to get out from under all the operational details that are keeping him from thinking about important strategic issues his unit faces. He should be focused on issues such as how best to continue to expand the business, how to increase cross-enterprise collaboration, and how to anticipate the fast-changing market. His solution? He tries to set aside two hours of uninterrupted thinking time every day. As you might expect, this tactic didn’t work.

Perhaps you, like Jacob, are feeling the frustration of having too much on your plate and not enough time to reflect on how your business is changing and how to become a better leader. It’s all too easy to fall hostage to the urgent over the important. But you face an even bigger challenge in stepping up to play a leadership role: you can only learn what you need to know about your job and about yourself by doing it — not by just thinking about it.

Why the conventional wisdom won’t get you very far

Most traditional leadership training or coaching aims to change the way you think, asking you to reflect on who you are and who you’d like to become. Indeed, introspection and self-reflection have become the holy grail of leadership development. Increase your self-awareness first. Know who you are. Define your leadership purpose and authentic self, and these insights will guide your leadership journey. There is an entire leadership cottage industry based on this idea, with thousands of books, programs, and courses designed to help you find your leadership style, be an authentic leader, and play from your leadership strengths while working on your weaknesses.

If you’ve tried these sorts of methods, then you know just how limited they are. They can greatly help you identify your current strengths and leadership style. But as we’ll see, your current way of thinking about your job and yourself is exactly what’s keeping you from stepping up. You’ll need to change your mind-set, and there’s only one way to do that: by acting differently.

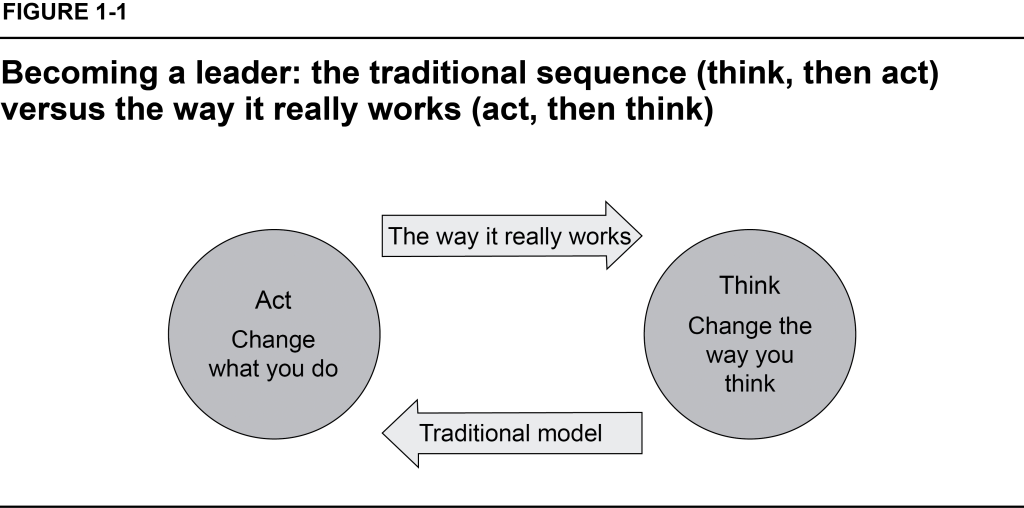

Aristotle observed that people become virtuous by acting virtuous: if you do good, you’ll be good. His insight has been confirmed in a wealth of social psychology research showing that people change their minds by first changing their behaviour. Simply put, change happens from the outside in, not from the inside out (figure 1.1). As management guru Richard Pascale puts it, “Adults are more likely to act their way into a new way of thinking than to think their way into a new way of acting.”

So it is with leadership. Research on how adults learn shows that the logical sequence — think, then act — is actually reversed in personal change processes such as those involved in becoming a better leader. Paradoxically, we only increase our self-knowledge in the process of making changes. We try something new and then observe the results — how it feels to us, how others around us react — and only later reflect on and perhaps internalize what our experience taught us. In other words, we act like a leader and then think like a leader (thus the title of the book).

How leaders really become leaders

Throughout my entire career as a researcher, an author, an educator, and an adviser, I have examined how people navigate important transitions at work. I have written numerous Harvard Business Review articles on leadership and career transitions (along with Working Identity, a book on the same topic). Interestingly, most of what I’ve learned about transitions goes against conventional wisdom.

The fallacy of changing from the inside out persists because of the way leadership is traditionally studied. Researchers all too often identify high-performing leaders, innovative leaders, or authentic leaders and then set out to study who these leaders are or what they do. Inevitably, the researchers discover that effective leaders are highly self-aware, purpose-driven, and authentic. But with little insight on how the leaders became that way, the research falls short of providing realistic guidance for our own personal journeys.

My research focuses instead on the development of a leader’s identity — how people come to see and define themselves as leaders. I have found that people become leaders by doing leadership work. Doing leadership sparks two important, interrelated processes, one external and one internal. The external process is about developing a reputation for leadership potential or competency; it can dramatically change how we see ourselves. The internal process concerns the evolution of our own internal motivations and self-definition; it doesn’t happen in a vacuum but rather in our relationships with others.

When we act like a leader by proposing new ideas, making contributions outside our area of expertise, or connecting people and resources to a worthwhile goal (to cite just a few examples), people see us behaving as leaders and confirm as much. The social recognition and the reputation that develop over time with repeated demonstrations of leadership create conditions for what psychologists call internalizing a leadership identity — coming to see oneself as a leader and seizing more and more opportunities to behave accordingly. As a person’s capacity for leadership grows, so too does the likelihood of receiving endorsement from all corners of the organisation by, for example, being given a bigger job. And the cycle continues.

This cycle of acting like a leader and then thinking like a leader — of change from the outside in — creates what I call outsight.

The outsight principle

For Jacob and many of the other people whose stories form the basis for this book, deep-seated ways of thinking keep us from making — or sticking to — the behavioural adjustments necessary for leadership. How we think — what we notice, believe to be the truth, prioritise, and value — directly affects what we do. In fact, inside-out thinking can actually impede change.

Our mind-sets are very difficult to change because changing requires experience in what we are least apt to do. Without the benefit of an outside-in approach to change, our self-conceptions and therefore our habitual patterns of thought and action are rigidly fenced in by the past. No one pigeonholes us better than we ourselves do. The paradox of change is that the only way to alter the way we think is by doing the very things our habitual thinking keeps us from doing.

This outsight principle is the core idea of this book. The principle holds that the only way to think like a leader is to first act: to plunge yourself into new projects and activities, interact with very different kinds of people, and experiment with unfamiliar ways of getting things done. Those freshly challenging experiences and their outcomes will transform the habitual actions and thoughts that currently define your limits. In times of transition and uncertainty, thinking and introspection should follow action and experimentation — not vice versa. New experiences not only change how you think —your perspective on what is important and worth doing — but also change who you become. They help you let go of old sources of self-esteem, old goals, and old habits, not just because the old ways no longer fit the situation at hand but because you have discovered new purposes and more relevant and valuable things to do.

Outsight, much more than reflection, lets you reshape your image of what you can do and what is worth doing. Who you are as a leader is not the starting point on your development journey, but rather the outcome of learning about yourself. This knowledge can only come about when you do new things and work with new and different people. You don’t unearth your true self; it emerges from what you do.

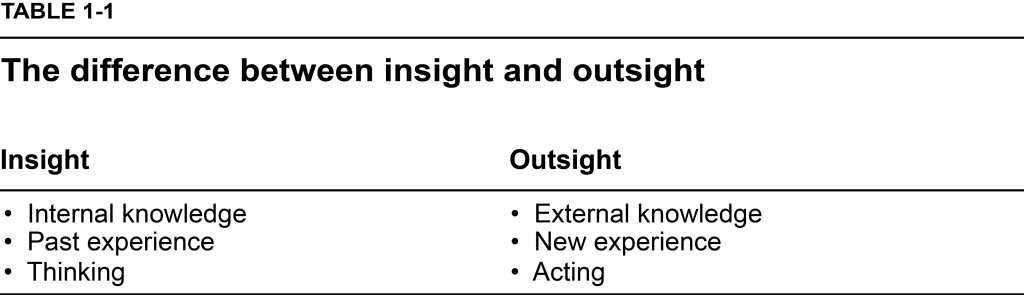

But we get stuck when we try to approach change the other way around, from the inside out. Contrary to popular opinion, too much introspection anchors us in the past and amplifies our blinders, shielding us from discovering our leadership potential and leaving us unprepared for fundamental shifts in the situations around us (table 1.1). This is akin to looking for the lost watch under the proverbial streetlamp when the answers to new problems demand greater outsight — the fresh, external perspective we get when we do different things. The great social psychologist Karl Weick put it very succinctly: “How can I know who I am, until I see what I do?”

Lost in transition

To help put this idea of outsight into perspective, let’s return to Jacob, the production manager of a food manufacturer. After a private investor bought out his company, Jacob’s first priority was to guide one of his operations through a major upgrade of the manufacturing process. But with the constant firefighting and cross-functional conflicts at the factories, he had little time to think about important strategic issues like how to best continue expanding the business.

Jacob attributed his thus-far stellar results to his hands-on and demanding style. But after a devastating 360-degree feedback report, he became painfully aware that his direct reports were tired of his constant micromanagement (and bad temper) and that his boss expected him to collaborate more, and fight less, with his peers in the other disciplines, and that he was often the last to know about the future initiatives his company was considering.

Although Jacob’s job title had not changed since the buy-out, what was now expected of him had changed by quite a bit. Jacob had come into the role with an established track record of turning around factories, one at a time. Now he was managing two, and the second plant was not only twice as large as any he had ever managed, but also in a different location from the first. And although he had enjoyed a strong intracompany network and staff groups with whom to toss around new ideas and keep abreast of new developments, he now found himself on his own. A distant boss and few peers in his geographic region meant he had no one with whom to exchange ideas about increasing cost efficiencies and modernising the plants.

Despite the scathing evaluation from his team, an escalating fight with his counterpart in sales, and being obviously out of the loop at leadership team meetings, Jacob just worked harder doing more of the same. He was proud of his rigor and hands-on approach to factory management.

Jacob’s predicaments are typical. He was tired of putting out fires and having to approve and follow up on nearly every move his people made, and he knew that they wanted more space. He wanted instead to concentrate on the more strategic issues facing him, but it seemed that every time he sat down to think, he was interrupted by a new problem the team wanted him to solve. Jacob attributed their passivity to the top-down culture instilled by his predecessor, but failed to see that he himself was not stepping up to a do-it-yourself leadership transition.

The do-it-yourself transition: why outsight is more important than ever

A promotion or new job assignment used to mean that the time had come to adjust or even reinvent your leadership. Today more than ever, major transitions do not come neatly labeled with a new job title or formal move. Subtle (and not-so-subtle) shifts in your business environments create new — but not always clearly articulated — expectations for what and how you deliver. This kind of ambiguity about the timing of the transition was the case for Jacob.

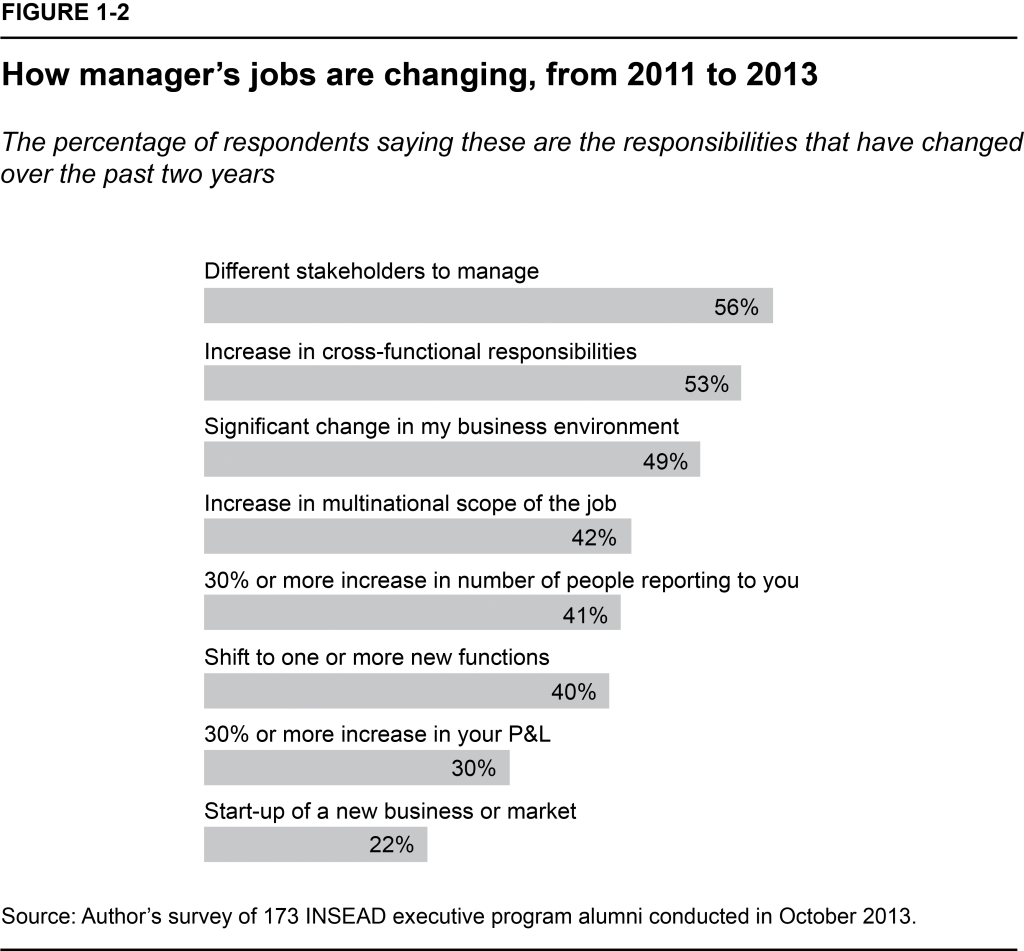

Figure 1-2, prepared from a 2013 survey of my executive program alumni, shows how managerial jobs have changed between 2011 and 2013. The changes in managerial responsibilities are not trivial and require commensurate adjustment. Yet, among the people who reported major changes in what was expected of them, only 47% had been promoted in the two years preceding the survey. The rest were nevertheless expected to step up to a significantly bigger leadership role while still sitting in the same jobs and holding the same titles, like Jacob. This need to step up to leadership with little specific outside recognition or guidance is what I call the do-it-yourself transition.

No matter how long you have been doing your current job and how far you might be from a next formal role or assignment, this do-it-yourself environment means that today, more than ever, what made you successful so far can easily keep you from succeeding in the future. The pace of change is ever faster, and agility is at a premium. Most people understand the importance of agility: in the same survey of executive program alumni, fully 79% agreed that ‘what got you here won’t get you there’. But people still find it hard to reinvent themselves, because what they are being asked to do clashes with how they think about their jobs and how they think about themselves.

The more your current situation tilts toward a do-it-yourself environment, the more outsight you need to make the transition. If you don’t create new opportunities within the confines of your ‘day job’, they may never come your way.

Read the original article on The European Business Review.